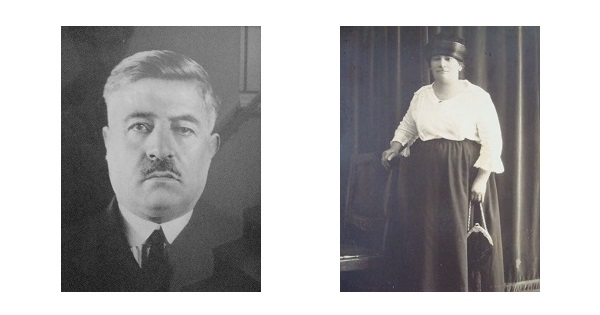

Photios G. Pirlioglou (Frank Perli) pictured left, and his brother Yamis A. Pirlioglou (Ernest Pirli)

The following testimony relating to Photios Georgios Pirlioglou, otherwise known as Frank Perli (b. Constantinople c.1894 – d. Syracus, New York 1972), his brother Yamis Anastasios Pirlioglou, otherwise known as Ernest Pirli (b. Constantinople 1902 – d. Syracuse, New York 1985), their father Iorthanis Pirlioglou, otherwise known as Jordan Pirli (b. Constantinople 1867 – d. Syracuse, New York 1928) and Iorthanis's mother Anastacia Pirlioglou was submitted through our online questionnaire by Photios's daughter, Frances (Perli) Sheldrick.

1. From which region of the Ottoman Empire were your ancestors from?:

My ancestors were from Constantinople (today Istanbul). On a 910 passenger list, my grandfather gives an address for his brother that appears to be 28, Sl Albss Ags, Constantinople.

2. How did their life change when the Neo-Turks and/or the Kemalists came to power? :

The Pirlioglou family was apparently well-to-do, owning property in the city as well as a farm. Anastacia, my great-grandmother, was an expert horsewoman. My father spoke of her many trips to get “wild” horses which she broke, trained, and sold. She oversaw the family properties, including the farm which was run by her son, Theophilos. They had apricot orchards and vineyards and raised horses and pigs. My father would smile as he recalled the horsewhip she carried and was not afraid to brandish, if necessary. She was fiercely protective of her family and Photios was her pride and joy. At one time, the nuns from the French School asked to take her daughter, Sophia (a brilliant student) to France to study, but Anastacia refused. I cannot recall my father ever mentioning his grandfather, and I assume he was deceased either before Photios was born or while he was quite young.

When Photios was quite small, he remembered sitting on the doorstep one day, watching a peddler walking down the street. As he watched, a Turkish soldier on horseback came up behind the man, drew his sword and sliced off the man’s head as he rode by, all without pause. At the same moment, Photios’ mother appeared in the doorway, snatched her son inside and slammed the door closed.

I do know that my grandfather, Iorthanis, listed Pireaus, Greece as his place of residence when he emigrated to the United States in 1910, but when or how he came to be in Greece is unknown. He listed his occupation as “photographer” when he came to the United States, but made his living in other ways after his arrival. The first records, his Declaration of Intention in December 1910 and a city directory listing for Providence, Rhode Island in 1911, show his occupation as a “cook.” By 1913, he was listed in the Syracuse, New York city directory as a fruit seller, and in 1923 as a “salesman.” It appears he first traveled around the eastern states and Canada in that occupation, and later, operated a candy concession outside the theater in Syracuse. Perhaps he thought he might return home someday, as he only rented rooms in the city and never remarried.

I also know that my father, Photios, was removed from school and sent to sea when he was about 13 or 14 years old – the age at which he would have been conscripted by the Turks. He worked on ships, traveling the world until he was in his early 20s. No doubt, because of his travels, he was very knowledgeable about many countries’ cultures and politics. He also spoke at least 15 languages, including Arabic and a Chinese dialect, and was fully fluent in Greek, Turkish, French, English and Italian. Since my uncle Yamis was said to have left Turkey on one of the last ships, he probably experienced more of the upheaval there – but he refused to ever speak of it.

3. Were they deported during the genocide? If so, when, where to, and describe their experience:

I had never heard my uncle’s departure called a deportation, but it was certainly so. He arrived in port at New York on 16 Oct 1920 aboard the Gul Djemal, among 1,000 Greek, Armenian and Jewish passengers. But, because some passengers lacked passports and others were ill, they were all refused entry until 02 Nov.

4. Were they held in a concentration camp or labor camp? If so, where was it located and describe the conditions:

Unknown – In addition to the family members who emigrated, there were others about whom I know little: Iorthanis’ brother, Theophilos Pirlioglou and his family and a sister, Sophia Pirlioglou, and probably more.

Pictured left, Iorthanis Pirlioglou. To the right a photo of his mother Anastacia Pirlioglou taken in Constantinople.

5. Did they lose family and friends? If so, how did they cope?:

Unknown. My father was a pragmatist. As a child, I once asked why he didn't go back to Turkey and claim his family's property. He simply shrugged and said "the government took it all." Since, at that time, I knew none of the history, I just assumed it was abandoned property and he never told me otherwise. Likewise, my uncle refused to speak of anything that happened before he immigrated. The most difficult thing is not knowing what happened to the rest of the family.

6. Did anyone within Turkey including Turks try to help them during the genocide? :

Unknown.

7. How did they cope emotionally with their genocide experience? Did it affect the remainder of their life? :

Since no one spoke of it, it's hard to know what their thoughts were. Both my father and my uncle lived productive, stable lives, married and raised families. My father died in 1972 and my uncle in 1985.

8. Did the denial of the genocide by the perpetrator (the successor state of Turkey) affect their ability to form closure?:

Unknown. They certainly didn't allow it to interfere with their day-to-day lives, however, I can only imagine the sorrow they must have carried.

9. How did they feel about Turkey after the genocide? :

The only specific comment I ever heard from my father on the subject was "the Turks can be very cruel people." He was not a man to carry hatred and anger, but he did follow world affairs and continued a life-long interest in history and politics. Occasionally, he would meet my uncle and other Greek men at the diner Ernie operated, where they would engage in heated conversations, but since they spoke their native language, I have no idea what they discussed.

Additional comments:

It is only since I began researching my genealogy, as an adult, that I’ve become aware of the events surrounding my ancestors’ emigrations. That they maintained stable, honorable, lives after such horror and deprivation is astonishing, and I only wish I could ask them about it. I’ve submitted DNA tests in the hope of locating other family members. Although there have been a few matches, none of us can trace our lineage due to the destruction of records, so we may never know our history.

Although we never fully understood the history of our family, both the impact of the genocide on them and the fact they chose to internalize rather than express it, was certainly carried into the next generation. Another family member feels great anger over those events and her life has been affected by that. For me, there is a profound sorrow for what they endured and carried silently, for the loss of people who ought to have been in our lives, and for the loss of our personal and collective history. While one side of my family tree is populated with literally thousands of people, the other side remains at less than one dozen individuals, with little hope that we will ever know more.

It has been suggested that my ancestors were at one time in central Turkey, and perhaps some came from the Black Sea area, but there is nothing left to prove or disprove that. My father’s correct birth year is unknown. I don’t even know my paternal grandmother’s name. She is listed variously as Anastacia/Agnes Kerilu/Kyrillos, and I believe Katherine was also part of her name. She died in March 1902, when Yamis was born and Photios was about 8 or 9 years old, whereupon, my great-grandmother took over the upbringing of her grandsons. My great-grandmother was a strong presence in my father’s life, yet I don’t know her maiden name, nor where or when she was born. Nor do I know the name of my great-grandfather or anything about him. Nearly all of our family history, prior to the genocide, has vanished.

Sometime after the death of his wife, Iorthanis went to Piraeus and thence to the United States, arriving in 1910. He may have traveled back and forth a few times, but his life seems to have been a solitary and lonely one after that.

My father spent so much of his life traveling the world, at first it seems he had a hard time settling down. At one point, he bought a tractor-trailer rig and traveled to nearly every state in the Union. He was in his late 40s when he met and married my mother. A few years later, they purchased a farm in upstate New York, where he lived out his dream – perhaps recreating his youth – raising animals, including pigs, cultivating huge gardens, and building a woodworking shop where he created many beautiful and useful pieces. I remember him as quiet and industrious, never still for a moment. His days began before sunrise, feeding the livestock, milking cows and performing other chores before leaving for his full-time job in the city, over 20 miles away. When he returned home, there were additional farm chores, in addition to the many home remodeling and maintenance projects he did. Even after retirement, he rarely ceased working.

My uncle, Ernest, left Constantinople on the Gul Djemal in 1920 for the United States. Upon arrival, the passengers were refused entry and the ship remained in port for over 2 weeks. Eventually, my uncle was admitted. He made his way to Syracuse, New York, where he was reunited with his father and brother (my father, Photios). Ernie married a Greek-American woman and built his life around the Greek community and the Greek church, which appears to have brought him some measure of peace.

There were other family members in Constantinople - a great-uncle, Theophilos Pirlioglou and his family, a great-aunt, Sophia Pirlioglou, probably cousins and my great-grandmother, Anastacia Pirlioglou. There may, in fact, have been many more. I have no knowledge of any of them.